I hope you’ll come visit.

Worry

That stupid dinosaur-crocodile hat is hanging right in front of me. “Hat” is a generous word. The hat is neon, and foamy, and cheap—much cheaper than the dollar I spent to be allowed to take it from the store. I pulled out my money and pictured the hat on my head, at work. I pictured any day suddenly like Halloween. I pictured calling it a crocodile when I need crocodile energy and calling it a dinosaur the rest of the time. I pictured the rest of me in dark colors. Instead, it hangs near my front door, with the summer scarves and the extra totes, and it has not been Halloween once since I purchased it. Since purchasing it I have written on the days when I “feel” like writing instead of the real good thing that is writing on a daily basis, through the feelings, through their lack. Writing despite x, y, & z. Writing because you don’t need to be composed in order to write. Like today, stuck indoors because of the fires and the heavy smoke and writing about the crocodile hat that fills me with rage because I know I would not grab it on my way out the door were I told to evacuate my home. I would grab other things, a few very clearly, fretting over many more. Rocks and seashells, some plastic trinkets I’ve had for 15 years, my sticker collection. I might accidentally forget my laptop, or one of the many bundles of instant photos we have lying about or tucked away. I’m stuck indoors because the state I live in is on fire and I’m trying to “write” without thinking “too much” of what I’m trying to write, trying to just “experience” the process and the act of writing without getting ahead of myself, and the crocodile hat upsets me because who knows what a dollar could do for a less selfish person, someone stuck outdoors and worried about getting ill or already ill and worried about growing sicker or maybe just done with being worried at all but really wishing they could buy a coke. A big fat cup of ice with sugar water to the rim. How cold and clear it might be in this difficult moment. There is so much pain in the world. In the store, I had pictured myself walking through long beige and blue hallways with my hat on, pretending to be none other than myself. As if it mattered. As if authenticity pursued head on could dismantle anything. I’m too busy thinking about myself to be myself, which was where my mind was when I purchased the hat.

~

I heard that the Almeda fire that burned northward from Ashland to Central Point, Oregon was started by a homeless gentleman. I heard that when the police arrested him, he said he was hot, and he was tired of being hot, and he thought if he started a fire maybe someone would take him somewhere with air-conditioning.

I slept much better last night, my mom said, though she’s still sleeping on the couch, which allows for a better view out her largest front window. I only woke up a few times looking for smoke.

Some people live whole sections of their lives awake at night, wishing there was a window between them and their worry.

Nobody’s sorrow is better or worse. Nobody’s fear. Nobody’s trauma.

Those statements above are true, but only if you look at them in the right direction. A sanctioned direction.

Look at my face through the window I sit behind and you’ll see it plain and true: worry. A girl’s affliction, no matter her privileges.

~

The chickens across the street don’t look worried. Not the squirrels or the cats, either. I worry about them all. I sit on a large purple chair, more expensive than any piece of furniture we’ve ever purchased and only inside our home because it is second-hand, and look outside as if hunting for concern on their little animal faces. I don’t find it. Which little animal faces am I most concerned about? I don’t find worry on the faces of the crows and I don’t find it either on the face of the woman with blue in her hair and earbuds in her ears, walking down the sidewalk, smoke billowing, everything dangerous, walking just like how I picture she walks on a normal day. The day is not normal and yet there she is. Nor do I see worry on the face of the man in the navy blue t-shirt smoking a cigarette and walking like his muscles told him not to stop no matter what. He looks upset. They always do, really. People like him and the woman don’t have their priorities straight, I think to myself in one of those pre-language thoughts, just learned instinct curdling in the areas of my chest not specifically occupied by a heart. Neither of them are wearing a mask. The man and then woman enter and then exit my view, and soon enough I am looking at the black and white cat across the street, a giant cookie made of fur, grooming himself on the front porch just like I’d picture him grooming himself on a normal day. Are you gonna be alright, cat? The feeling is like a light beaming out of my chest.

The window I look through gives my day the much needed semblance of a container and a routine. It makes me feel like I belong somewhere, and that somewhere is not out there.

All people have voices, and some people have the space in which to use them, the default public setting of being heard. Some people are empathizable. Easy to feel across the distance.

Which comes first: the chicken, or my worry about the chicken? The feeling of crossing a distance in order to empathize with you, or the sense that you’re already close enough for my empathy to make it over there?

The chicken is on the fence now, one of them. The other one has taken to sleeping precariously in a tree. More reasons to worry—I basically manufacture them in my spare time. I care about the chickens with no effort at all, a bursting feeling.

Some people sleep in their cars every night. Some of those people are the “lucky” ones.

If you are well, and you encounter a traumatic moment, the city might rally. Especially if you’re graced with social privilege. You might be greeted with opportunity and given access to resources. The community will likely “feel” your pain.

If you are not well, your life a string of traumatic moments, then it sounds like this is actually just your baseline and you will be difficult to empathize with. What did you do to end up here, anyway?

I get used to the repetitions—that’s what repetition does: primes me. Deludes me and the outer world right along with it. As if pattern diffuses a malicious thing. As if form trumps content. Normalized expectations sing, and I’m sad to confess I get used to the background music. I would like to expect a less patterned, more imaginary world, and trace it until it is a real shape. I want to be shocked by the shocking things that continue to greet the daily sun. I want to “do” “something” “good.”

The cat across the street is a very big cat. But the problems are bigger than the big cat.

The chickens are the only two chickens I know, so they constitute the place where my worry pools: on the fence, in the tree. “Ignorance is bliss,” except this is only true for the beholder. What about the chickens I don’t know? There must be more than just these two. How will I know which others to worry about?

The gray chicken has leapt into the tree now. Before tucking himself into the safety of an inner branch, he floats on the outer leaves and flowering parts. He looks like an apple. He looks like something to pluck. He is a guitar, and a whole barnyard, and the entire ocean in a single drop of chicken. He is gray, with the requisite yellow and red parts. The white one, always anxious being left behind, only gets as high as the mailbox and then stares at his ascended partner. There used to be three chickens, actually. These bird-dinosaurs are the tip of the iceberg. There is so much more plucking and leaping and breathing and walking and sleeping and wishing out there. I notice what I notice. And what I don’t notice? I don’t notice it. Which doesn’t mean it isn’t there, hovering, maybe camouflaged, scared or hot or looking for a window, maybe even something near a breeze.

Sir,

an elderly woman called out to me, what she thought was me, and indeed it was except I was no sir. Could you help me with something heavy? I said yes and brought my boyfriend out instead, as if supplying her with the more accurate version of her request, the sir she wanted. Are greetings just floating signifiers, or made of actual content? I suppose it depends on the context of interpretation: artist or viewer. If the woman’s intention was to produce invitation through contact, then it worked: I understood her request immediately, didn’t look over my shoulder for the others, would not have benefitted from clarification. Who, me? A few sentences ago, I almost wrote something about, “polite contact.” Is it ever polite to misunderstand someone? To brand them with your personal expectations of how the world works? The question assumes a superficiality antithetical to community, forcing “inclusion” to revolve around sight, the status quo of all human senses. Understanding demands space for difference and curiosity, which flower with appearances, sure, but only by firmly hidden roots, all the grounded stuff you can’t expect to see. To understand someone is to know that there will be truths both contradictory and unwitnessable. The only way out into the broad arena of true recognition is therefore through questioning and apprehending, and the elderly woman did both. She suggested a world in which my gender presentation and my biological sex may not reinforce each other, and she was polite to me regardless of the potential affront that stalks such incongruities. But by now, I am mistaking the viewer’s reception with the artist’s intent, imbuing her words with stance and premeditation. She simply thought I was a boy.

I brought my boyfriend out instead, without asking for his availability, having translated question into obligation. This woman needs your help. In the face of misunderstanding—was I embarrassed? feeling defensive?—I brought a man to solve what was then reinforced as a man’s problem. Why didn’t I just help her? Because I am no sir, and my drive in that moment to establish the few attributes I lack overpowered the possibility of the many I could contain—strength, fluidity, playfulness, understanding (the woman was, after all, quite old), or just being a good neighbor. I picked up all the implications of her greeting and found a way to carry both much more and much less than the situation asked of me.

Men have always turned “weight” into opportunity: muscles tasked with function, they rectify absences, fill holes, provide height when gravity bullies and receive praise through their lifted objects without having to become them. Weight, a woman’s problem that demands modification and restraint, becomes, in the context of dudes, a thing to absorb or pick up. I am engulfed by manly distinctions, a flame too close to my back. If words sometimes stick to the wrong body, which is modified by which? Why did I say wrong body instead of wrong words? Perhaps I could only prove I was not a sir through comparison and contrast, by taking the woman’s question seriously enough to insist I could only supply, but not become, the answer. When born of insecurity, need sometimes does nothing but highlight its own relativity: if I must find a man in order to establish my own lack of manhood, what does it mean to be a woman? I am not a sir, but perhaps not inherently a she, either.

Even landscapes can be made of habit and instruction. Land goes here, sky there, keep the horizontal median plush and predictable. But gender is pure context. Things weird or new look out of place against the backdrop of all that’s already been established as what is. Trace a line far back enough and you eventually find an initial point of contact between pencil and paper, context of the origin. Is it ever polite to misunderstand someone’s gender? If things are made up, and the social world is constructed, and humans are capable of change and growth, then the question is nonsense. Only when misunderstanding morphs into insistence does confusion become dangerous. But in the context of an elderly woman wearing thick glasses, crossing the street near our lilac bush and discovering my young, accessible body: it is simple reflex gone mildly rogue.

When people ask me questions, I sometimes wish to know their long-term expectation before answering. As if truth requires context or carries a faltering sense of responsibility. By truth I mean gender. Full of holes, defining itself against others and itself and the new day.

Sea Sick

To be willing to grow, you must be willing to be, at this stage, at least a tiny bit wrong.

I said wrong, not different.

When something or someone different has to be vouched for as being “okay,” “alright,” “I mean it’s fine if that’s what you choose…,” you are indicating a system which demands that perceived otherness or badness be accompanied by language. “She’s fine.” “I guess that’s okay.” Despite, despite, despite. Lifestyle, relationship, tone, design. Shape, size, etc.

My point is that it is a privilege to move through space unaccompanied by language.

To not alarm anyone by your need for explanations.

To be a disseminator of the language of approval is basically to disguise judgment as tolerance.

Some things don’t need to be said. Or shouldn’t have to be. A more tolerant world would, in fact, be mostly quiet.

I suppose oxygen is okay. I mean breathing is fine. It’s alright if a “deep breath” is what you prefer. But I wouldn’t take one myself.

Who says a single person needs to understand everything?

[ People who feel the need to vouch for otherness.

People who refuse to couch their fatherliness.

People who peruse and who mouth and who cover up the rest of us.

Here, let me explain this to you. I know how badly you want to understand. ]

There are good things in the world that you’ll never understand:

How the sun works.

What gives water its blue-green precision.

Your birth,

or where and when excitement is distinctly born.

You want to understand because you can’t distinguish love from facts.

You can’t love me without thinking about me. Thinking through me. Right through the middle.

And what’s the point, you say, in thinking, unless you’re gonna do it all the way? Think until you understand comprehensively.

So that when you’re done thinking, you tell yourself you’ve arrived at comprehension. F-a-c-t.

You can’t see the rooms the doors of which you haven’t even opened.

You can’t see the frog in your throat.

There is a frog, and you love him. You want your love mirrored by the cold shape of unmoving, published statement. You want to understand love from the inside, as if it were capable of being emptied out. To dissect the frog, it must be dead. Then you’ll know so much about him. Your thoughts about the frog will be buoyed by

your own objective knife, called apprehension.

I am working on healthy boundaries:

Distinguishing no from yes.

Leaving a room when I must.

Not laughing out of habit.

Not picking up weight that belongs to another.

I watch “love” and “understanding” meander down the street, side by side.

Not interchangeable, but in many ways, yes, parallel.

And when the two diverge, I sometimes maintain my grasp on the former, let my thinking brain go on ahead a few more blocks, however far it wants to go, while we stay behind, me and my heart, no longer wishing to replace presence with scrutiny.

The thinking, at times, interrupts the being. Segments it. Blood-letting, a slicing motion.

It says:

I think it’s okay. I mean, what you’re doing. I suppose I think it’s fine. If I can just see it from the inside first, take a closer look at the stuff naturally kept away from me, I think I’ll feel better releasing it back into the pond.

How To Raise Kids Without Having Any

Contemplation, strictly speaking, entails self-forgetfulness on the part of the spectator: an object worthy of contemplation is one which, in effect, annihilates the perceiving subject…All objects, rightly perceived, are already full.”

~Susan Sontag

How are you supposed to be a person before you’ve become yourself?

When you’re 9, 10, 11 years old, handcuffed by the impending sea change of hormones and the inevitability of messing up, it’s hard to overemphasize the value in looking at everything that exists outside your boundaries and then making some hard choices about where to cross over. Do you hear what I’m saying? One becomes oneself by first loitering and failing, by drinking the strange potion of doing bad things and making what will eventually be seen as, in one context or many, mistakes. Bad because not allowed, mistakes because never again. You prank people, you send a neighbor’s trash can barreling down the street, you reveal words to friends told to you by other friends and find yourself, by the end of the week, lonely and speechless and bored. You judge people and turn away from opportunities. You hang out with peers you’re “not supposed to” and drink things you’re “not supposed to.” You do little at school, and then even less; you do bad in life on purpose. If the greatest thing about being 70, as May Sarton once told a stunned crowd, is that you are more of yourself than you’ve ever been before, then the shared truth of that fact is that you are hardly so when you’re young.

So what is the job of a parent? And how do we ensure that the duties are fulfilled when the nuclear unit, already so treacherous a shape, has exploded, leaving kids parentless, and single parents stretched beyond the thin membrane of their already tapering selves, and children vulnerable to the strange spectrum of homeless <—-> home after home after home, the displacement caused by hyper-placement, the unraveling of home from a house to a street, a street to a city, or one couch to another, night after night? Kids bounce, or they run, or they are placed elsewhere; or else they share space with numerous others and find themselves shuttled back and forth between visitations and conflicting schedules, their lives unfolding not in bedrooms and classrooms—the privilege of clearly defined, designated spaces—but filling up whatever empty cracks and corners they can sneak into. Bouncing and rebounding, running and shuttling: all those gerunds are the side-effect of unintentional splitting, whether it be sudden death or the earth opening up around a couple’s previous commitment, how we adults can sometimes change our minds, or leave our minds perfectly still for too long, only to find younger generations swallowed whole by the consequences. Abuse, neglect, or things simply catching up with us, which happens a lot, in my experience of being an adult: one day I’m doing the chasing, the next day I’m being chased. And while I never moved through foster care myself and, with a few minor exceptions, generally knew where I’d be sleeping each night, I was nevertheless a child of divorce, unwellness, and adults who refused agreement and compromise; of the shattering of normality, how we all pretended, according to our ages, that we could function through to the other side of whatever it was that consumed our household for all those years.

It wasn’t until I reached my 30s that I found Nora Ephron: “…infidelity itself is small potatoes compared to the low-level brain damage that results when a whole chunk of your life turns out to have been completely different from what you thought it was.” The brain damage was, is, mine, and the infidelity my father’s, who brought a whole slew of damaged and damaging women—in image, in real life flesh—into our household, exposing me, at the earliest age I can remember, to the abusive notion that my gender could achieve value only through becoming sexually desirable to a certain type of man. Achieving, becoming—in other words, gender troubles. The thing about gerunds is that they take all the action out of the verb, they function by relinquishing their motion for the stillness of a noun; they hold still when you might’ve expected them to go forward a little, and I can’t think of a better way to describe being young and feeling out of control than that.

So what is the job of a parent, a support person, a trusted adult? You can’t help a person become themselves any faster than nature and empowerment allow. But you can help a child understand that they have options, that they can make things exist that did not exist before their making them. That they can be curious, fail broadly, try again. There’s a lot of time for trying again when you’re young. But the best way to encourage the person a child will become is to model the doing, the making, the being; in other words, the personhood. Kids see how we act and what we see, they learn through the act of witnessing. The job of the guardian is to foster spaces wherein youth may witness life’s bigness, fortified by patience and humility and, above all else, a creativity that growls over perfection’s whisper.

The other day, killing time in a doctor’s waiting room, my partner recounted some of his teenaged hijinks to me, spoke of how he and his friends once rearranged all the lawn décor on a series of houses a few streets from their own. The doctor hadn’t called me back yet, so I reciprocated by mentioning the time I once shot a bb gun into a school window; or how I’d stayed the night in a den with a bunch of seniors when my mom thought I was already home, how I had a man call the school and claim to be my father, excusing me from the day. Some of it worked out—by the skin of my teeth, I avoided certain natural consequences—and some of it didn’t (my mom had already called the school 30 minutes before us, looking for me, worried sick). None of this stuff has any bearing on the person I am today, beyond the simple and extraordinary fact that she was once me, and that she survived.

Posturing, denial, repression. Our adult methods for making sense of a chaotic world grow sophisticated as we fall more into ourselves, as we army crawl into the lives we’ve chosen. As you get older, you learn how to do more than just casually tiptoe across the boundaries you encounter and begin to harness the full force of your unique volition, sometimes setting new, expanded boundaries. Survival depends, at least in part, on a relationship with your younger self: that you learn to let the word “forgiveness” sit lightly on your tongue, that you understand how utterance conjures the good ideas which, in turn, become actions. But survival also depends on the experience of being young, being her, and having at least one adult who will listen to your new feelings and less good ideas and transitional states of mind and, rather than dismiss them, will take them no less seriously than what’s found in the heart of every single adult who, alive and mortal, sometimes changes their mind, too. Nobody stops growing, and that’s the shared intimacy of life and death across all generations, two sides of the same fabric—the same seam, the same pattern.

To alienate a young person in their journey toward becoming themselves is a form of abuse. To pretend their struggles are not normal, to react with shock more than curiosity and understanding, to try and replace steadiness with speed or vice versa. It is to close them up into little clamshells, to pretend they aren’t the same creatures who will one day make pearls of themselves, their feelings real in the same real world of your own.

We punish kids for not being better, yet we’re full of shock when, over time, they change. “You never used to like [fill in object here],” goes the classic parental saying, or, “you used to be so __________,” always said with a touch of ridicule. As if we want to take our little loves and freeze them in place at our own shifting will. Dear reader, how many pieces of your own comprehensive heart do you show the world, and when are they static? How often is your thought process conflicted, or full of thin holes, or not anything like what you’d once expected of it?

We can support youth, in professional as much as personal capacities, by showing them what it looks like to be a model of misfit survival. It is nothing short of magic to watch the walls go down when a young person reveals a dark sliver of themselves and you, adult person with power, don’t flinch. You understand, you remember, you empathize. It’s hard to make hard choices in frail circumstances, you think to yourself. Sometimes, survival is the only eligibility requirement when seeking a coping mechanism from a dark place, and you recall this by reflecting on your own once-bad choices and the ways they kept you reaching into tomorrow. Validation is a big, fraught word, but at its base, all it requires is understanding, any version of it, between two people.

What youth need from us: witnessing, contemplation. And I do mean the Sontag kind, where you recognize the worthiness of a young person to the point of momentarily forgetting about yourself; this is the reward of working with youth: an “already full” heart, how the stewardship of children and teens requires paying such complete attention that you can’t help but fill up with a tenderness bigger than yourself. And when the obstacles are larger? More and more consideration. And when young people find themselves inhabitants on the spectrum of homelessness <—-> home after home after home? Place and environment are things every young human has the right to count on, but care and open communication are places, too. Nonjudgmental language is an environment. Who is that person you could turn to all those years ago, when you were young and scared and needed someone to trust, someone whose lineage wasn’t bound up with yours? Think of that someone who kept you afloat. Now imagine under whose lifejacket you might be the ocean beneath.

Common Ground

“If there is a reason,” said Representative Greg Walden at the Wasco County town hall on March 15th, 2019. He was describing the only circumstance in which a child might still be rightfully separated from their family at the southern U.S. border, and it’s the kind of comment, devoid of information but full of stance, that turns even my most respectful impulses into immature outbursts of laughter.

There are reasons for everything: for me to care about climate change above all else, and for the gentleman across the aisle to deem national security a much greater issue. For the mother of six to refuse vaccinations that caused so much harm to her family. For me to refuse God with the same conviction through which some of my neighbors, co-workers, or friends adore him.

The point of a town hall is not, ironically, to find common ground in all this—or rather, it can’t be, not within the current set-up of how we communicate with each other in public spaces. Though Walden struck me as slightly more behaved than he was during his last trip through The Dalles, so many of his words still rang like prepared soundbites, so that listening and nodding along to each community member’s question or comment only belied his own silent crafting and culling of data. Indeed, his batch of digital slides, rather than signaling extreme preparedness, felt instead like restrictions on where the conversation was allowed to go. This created a tone of constituents needing to accommodate the representative versus the other way around, all of us shuffling over his bullet points to try and get our specific, unaddressed concern into his line of sight.

I’m not above the problem. As each citizen took to the microphone, I noticed myself examining their clothes and haircuts, who they smiled at or when they shook their heads with a heavy no, trying to figure out if they were my people or not. It’s precisely this method of judgment that keeps agreement and disagreement in little calcified boxes, separated by the illusion that people could ever naturally and wholly be just one thing or another.

Walden is a figurehead of that illusion. He must learn to listen to the diversity of his constituents the same way I must better witness my peers: as complex and multifaceted individuals, full of the same capacity for passionate, contradictory, and informed sets of reasons as my own brain and heart. We are all capable of misunderstanding; holding a position in office does not imbue such errors with authority, nor magically exempt the congressman from critical thinking and self-doubt in the face of something he doesn’t recognize or can’t explain, whether it be a species or a number or a lifestyle. The only person truly qualified to turn something away is the person who has spent time and energy desiring first to understand it. And it is this fact through which I define “hatred” as a feeling devoid of all intimacy, the easiest and laziest and least informed reaction a human being is capable of. Just look at our president.

I am sad when I leave a town hall like this one, where hatred bubbles up in little pockets of the room and stops most of us from true contemplation. The person at the front of the room has signed up for the job of surveying and advocating for the communities he represents, and his partisan refusal models one of the most insidious myths of American progress: the illusion that it is lost, not strengthened, when you consider the other side.

To embrace difference, to find a common ground that holds space for everyone’s feet, means entering territory not always accounted for by the prepared data. It means admitting when you don’t know, and owning the inevitable blind spots in your research. It means, most fundamentally, admitting humanity, which is always also an admission of mortality and which, in turn, is always also an admission of room for growth—for something other than what you and I already are.

My challenge to Walden is to model active, bipartisan listening: to not grimace at the mention of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to not deflect concerns about carbon emissions by pointing out that we’re emitting carbons “even right now, by the way.”

There is always a reason, and that means there is always a context, usually many, worth considering.

The Uses of Grumpiness

(Note: The following essay also lives in the winter 2019 issue of Culturework.)

Consider the grammar of being human—how the body infiltrates, or punctuates, or rests. Verbs and proper nouns and idealizations spin around the axis of grumpiness, shaping its signature bend, adjective turned identity, twinned self of the quiet body trying to speak up at its own sighing pace. Grumpiness is a kind of preposition, which governs the relationship between two distinct bodies. It locates, it expresses and, in the best of circumstances, it modifies. It is both form and content, shape of how I march down the page as well as my reason for showing up, a pattern for these tempered, ill-fitting days, when it’s hard not to think about negativity and pessimism and anger. The nouns pile up on my tongue, in my sentences.

These days, Audre Lorde’s name is practically a buzzword, bouncing around social media and excerpted strategically in articles and newsletters with “self-care” in the title. There’s Lorde’s poetic cry, demanding self-efficacy, arguing for the necessity of a compassion that gazes inward at its own oppressed self, even or especially in the face of racism and sexism, of blemishes and dry skin.

I have no problem with self-care, at least as a concept, even when it just means skincare—I pursue it myself, and in fact I am inclined to say that citing Lorde within discussions of lifestyle trends, just to be extra cute about it, is a lot like sneaking some romaine between layer after layer of cheese and mayonnaise and ham. It is inclusivity pursued slowly but pursued nonetheless, through the basic tenet of just being more familiar with something else, of being, at the very least, less caught off-guard by its presence. Trend-driven or otherwise, that more people know the name of a black lesbian scholar and poet-librarian is, fundamentally, a good thing.

Still, I am frustrated by appropriation and by the refusal of context, just like everyone else is.

And I am reminded that besides being a warrior for self-care—for literal survival, in her case—Audre Lorde was also a protector of anger.

And so was Andrea Dworkin: “My hatred is precious…I don’t want to waste it on those who are colluding in their own oppression.”

And so is Bhanu Kapil: “Let your fear adore you.”

And again Lorde: “My fear of anger taught me nothing. Your fear of that anger will teach you nothing, also.”

I am frustrated, too, by my own limited skills on the page, that I must co-opt anger toward racism and discrimination, must quote from poems that advocate for the voices of marginalized groups, anger dedicated to silenced women of cultures not my own, regarding circumstances I’ve not had to endure, in order to address my own obstacles. Here are the things that, as I write this, I am angry about: stupid trainings, where facilitators do not enact the things they are teaching; co-workers who talk over and interrupt and then ignore me; wages that leave me broke but not poor; rude doctors; rude rejection letters; rude people at the movie theatre who forget or never learned how to share space.

Most days, it is a privilege to be upset about such things. Yet I refuse to believe that anger exists hierarchically; in fact, add to my previous list that I am mad about one-upsmanship, mad in the face of this or that, mad when people think the quickest way to empathy is by responding with their own more or less similar story. The farthest, slowest way to empathy is through more of the same kind of talking. A world more empathetic than this one is comprised of a great deal more listening, nodding along, moving your hands and your shoulders and your head with the rhythm of absorption. Active, comprehensive listening.

In fact, it was only after I’d attended last year’s Womxn’s March, here in the small, very red, trying-so-hard-my-heart-could-crumble city of The Dalles, that I found myself full of ideas for how I could have decorated my sign, one of them being the following:

HOW TO BE AN ALLY:

#1 Shut up

#2 Listen ❤

The heart would’ve been an obligation, but it always is.

Anger, explains Lorde, is not just the valid and healthy feeling we are experiencing but the thing itself to which we are responding. In this sense, anger is both internal and external, dynamic and living. It is born of the body, an expression to be cradled and protected, and it also floats about you, interfering with and directing one’s movement. Address it or don’t, it will shape the air surrounding you regardless.

So much of acknowledging anger, of making space for it, is about highlighting what has remained invisible for too long, about finally putting a face to the invisible names long accumulating in our downturned mouths. Of productively challenging the notion that silence and invisibility are slim beasts of poor constitution, as if certain forms of abundance can swallow you whole and then become something else entirely, something smaller.

Anne Sexton: “Abundance is scooped from abundance yet abundance remains.”

In my reading of it, it is one of Anne’s most generous and hopeful lines, in dialogue with Lorde’s understanding of the direct and crucial relationship between anger and hope, between lived negativity and active growth.

Walking through the sad colorful streets of downtown The Dalles with the only thing I could think of at the time written on my sign—“Patriarchy Shmatriarchy”—I was overwhelmed with the comfort of being inside a temporary community that could safely and willingly hold any individual manifestation of anger, snarky comments, shouting or protesting, from any single body that felt like yelling; how easily certain forms of anger can come to look like celebration, and vice versa, within a designated, cooperative space.

Anger can be a thing worth celebrating; so too can every single instance of a name like Audre or Andrea or Anne falling out of a person’s mouth, sometimes framed by glowing, supple skin.

It is with all of this in mind that I commit finally to the page my status as an advocate for grumpiness and its many uses. There are only so many ways to express disagreement in an engaged, unrefusing manner; it is grumpiness that carves out space for such feelings. When I am grumpy about a thing, I am usually most successful in achieving authenticity. When I am grumpy, I am both gentle and blunt, both close to you and considerate, even protective, of the distinction. God knows I have lost myself in too many moments of caving in, of ultra-accommodation, of confusing love with cathexis (bell hooks), of confusing love with the soft turn of a mouth that says mmhmm and laughs at everything, in perfect horizontal reassurance. God knows I’ve had enough of unwelcome horizontal reassurances.

This is all just language, but it helps to name one’s experience in conveyable ways. For example, “mansplaining” (Rebecca Solnit). For example, the messages on every cardboard and construction paper and taped, glittered, last-minute sign I walked beneath at the Womxn’s March in The Dalles.

For example, that which I call this very precious moment of my disapproval made public, my whole entirely nameless body that says, you don’t have to be loud or distant to be upset. You can be close and intentional and full of care, bone and organ and muscle. With ease, you can pair grumpiness with intimacy.

The lack of speed which informs my grumpiness makes time and space for slower thinking, for long moments of intentional silence. For contemplating the understanding that my grumpiness demands and which, in turn, it may need to afford. To be grumpy is perhaps to be in a hurry about nothing other than the initial moment of grumpiness itself, to rip an aesthetic hole in the fabric of the polite day and refuse the social shapes collecting dust before you.

Sometimes, being grumpy is the best way I know of to be my most authentic self, in a room full of people doing things differently, maybe loudly, sometimes aggressively. Grumpy is for people who don’t want to be aggressive but still want space to be mad, people who, first of all, want space.

It’s okay to not be okay, and it’s okay to be engaged and okay and not okay and grumpy all at once, all those feelings that, when resisted or ignored or feared, turn the color of apathy.

An ideal morning would perhaps include coffee on the front porch, a book I am exactly in the middle of, long stretches of silence, and a grumpiness that sets its own remembering pace, chirping and squabbling along with the day.

At work recently, I felt so grumpy as I found myself in a room full of educated adults, snack food, and good intentions, most of us sitting in rows near the back while one or two of us stood in the front, natural leaders. Extroverts and people with authority like to ask questions with very specific answers tied to them, and sometimes when you don’t give the answer they’re looking for they proceed to help you get there. Help as in prod.

Dear extroverts, talkers, teachers, if you have the answer you’re looking for already, it’s time for a new question. If you think there’s no space for productive negativity, for healthy anger, for grumpiness in lieu of perpetual grace, then there’s no hope left for you. The irony of words is that they sometimes suggest contradictions that apply mostly to the form itself, that they can practically invent their own falsely stable definitions. In order to name my grumpiness, I will name, too, all its siblings: concern, self-doubt, resistance, imagination, embarrassment. Grumpiness is the most natural, most organic extension of my care, content directing its own form: precious, adoring rage, it’s face turned toward the day.

Keep going

This or that

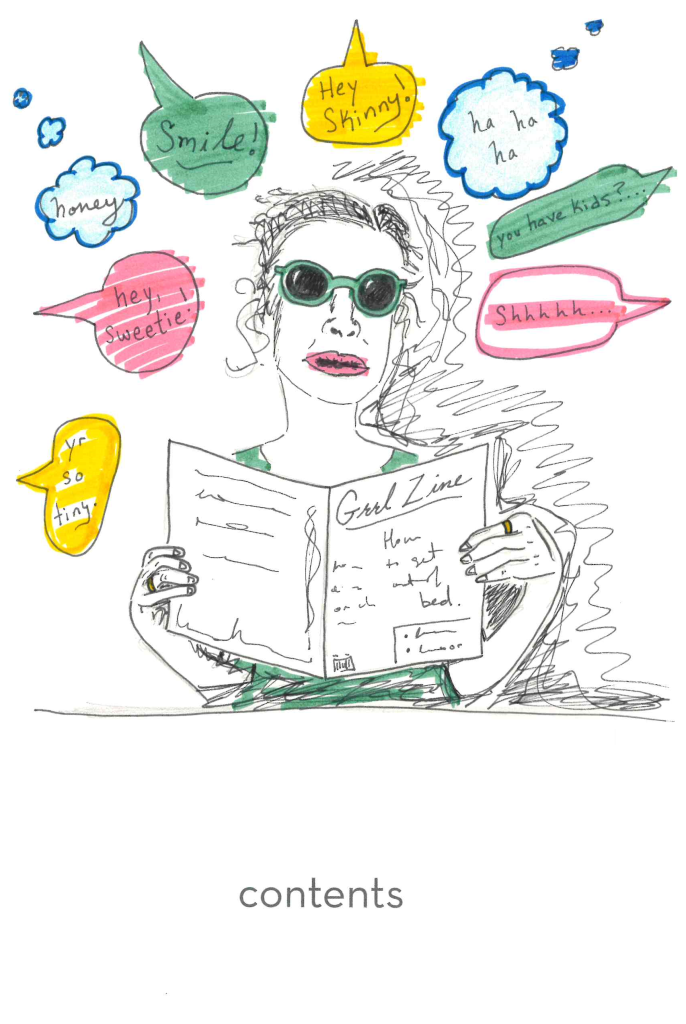

Contents